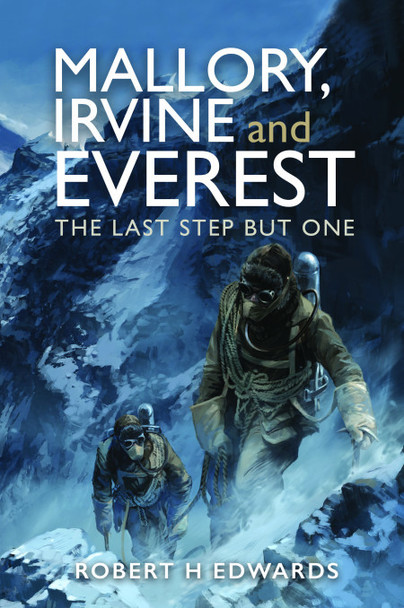

Were Mallory and Irvine the first to climb Everest 100 years ago?

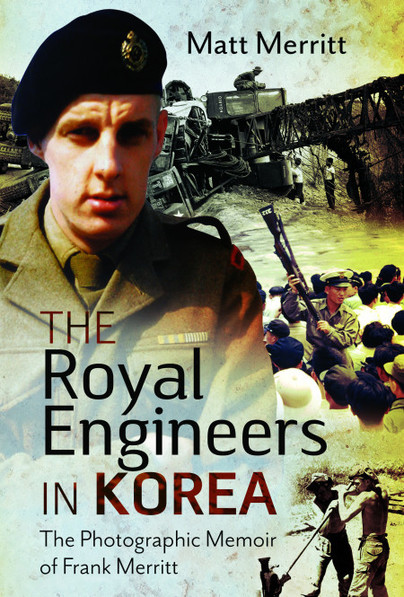

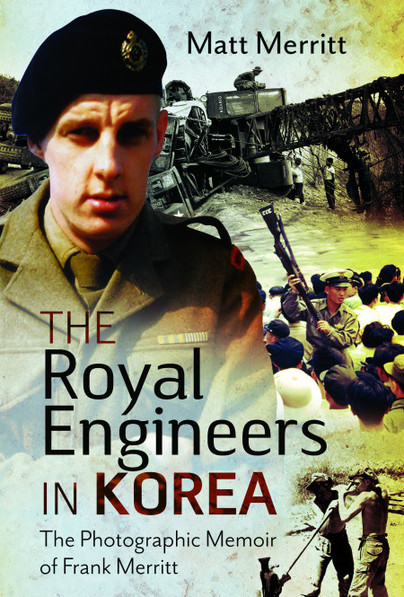

A Korean Wild Boar in the Royal Engineers

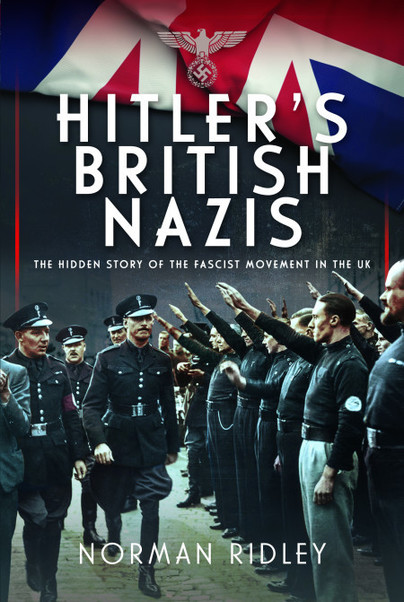

The Austrian Princess and the British Lord

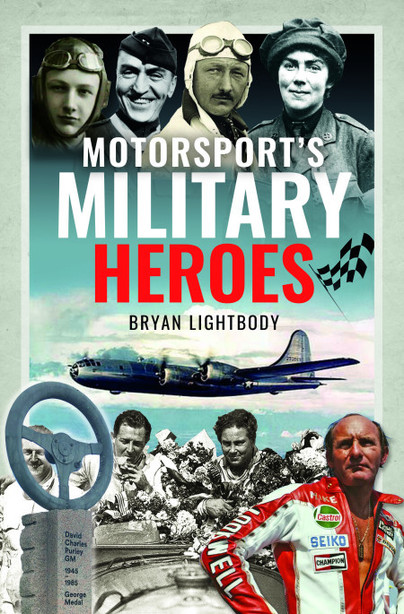

As previously highlighted, my enthusiasm for historic motorsport coupled with writing and battlefield guiding lead me to produce (what I hope will be) Volume one

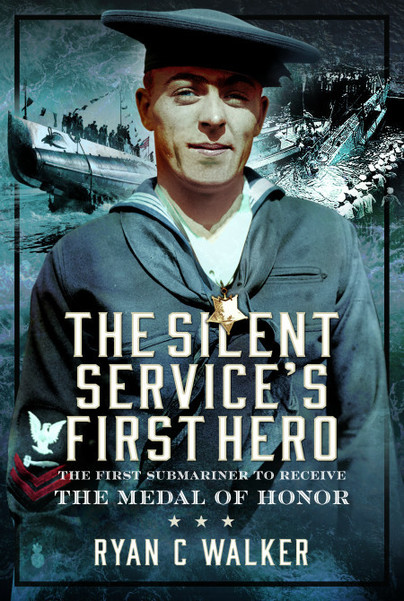

Henry Breault Medal of Honor Centennial, March 8, 2024, Proclamations, Resolutions, Events, & Other Rememberances

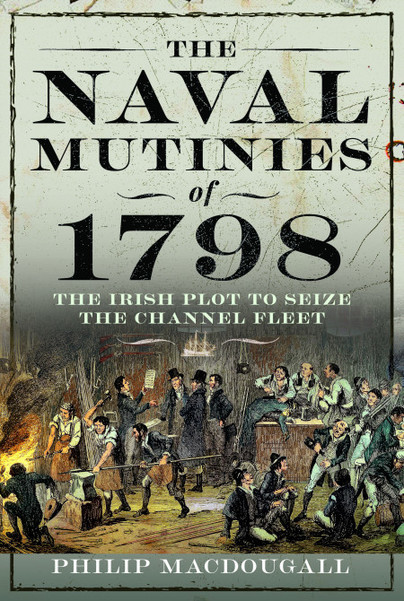

The Naval Mutinies of 1798 Philip MacDougall, Ph.D.

British Legion chairman Francis Fetherston-Godley visits Dachau

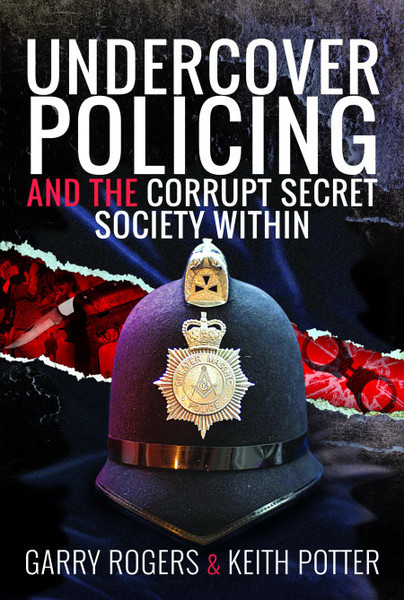

“There is nothing more l can add to the conclusions that you already have”

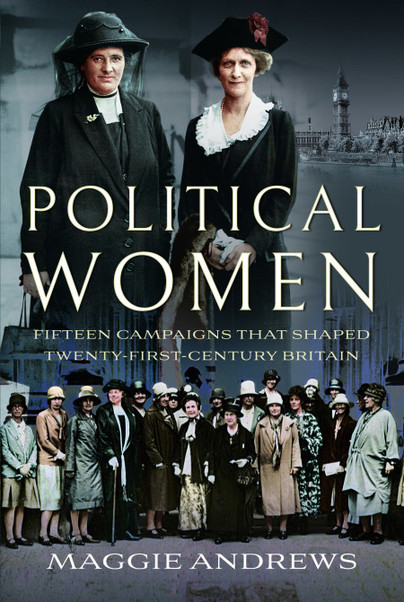

5 women’s political campaigns which shouldn’t be forgotten

View More